Photo by Chi Essary

POETIC LICENSE

Artist Studio Visits by Chi Essary

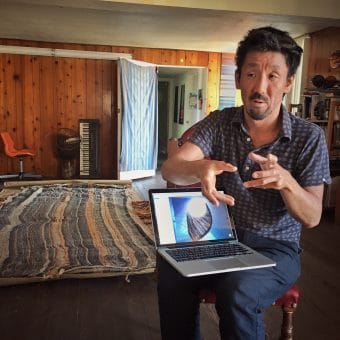

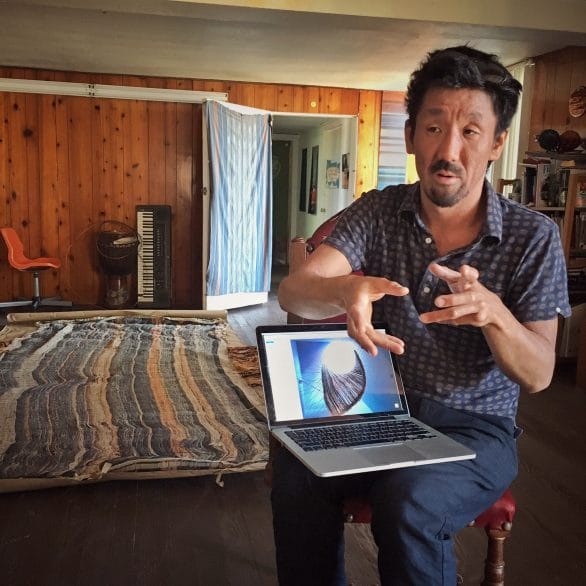

Shinpei Takeda was born in Japan. At age five he moved with his family to Germany, where he grew up in a secluded Japanese community and learned little German. He moved to the U.S. for college and now lives in Tijuana, traveling seasonally to Germany and crossing the border regularly to San Diego. Essentially he is straddling two borders, regularly speaking three languages and living between four cultures – a truly multi-national person on a modern-day scale.

Looking around his long, retro wood-paneled studio, I see Tijuana sprawling out below a window with its HUGE Mexican flag indolently billowing over the city. Small segments of sonograms from his Alpha Decay series, about Japanese survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, are tacked to the walls here and there. Laid out on the open floor is a large rectangle of loosely yet meticulously woven wool threads. He pulls at it from one side and then another as he prepares to roll it up while he explains the sonograms. For the Alpha Decay project, Takeda transposed hours of recorded personal stories from the survivors of the A-bombs into sonograms and created a series of installation pieces that were shown in locations around the world, including Beijing, Tokyo, and Mexico City. Personal trauma also figured into his subsequent installation series, Beta Decay, in which intricately woven strands of wool yarn symbolized the many threads and knots of trauma within our psyches, families, and communities. “I try to deal with how to listen, how to understand, how to ‘download’ these stories to ourselves and others.”

In the large installation piece Beta Decay #3, which just won Takeda the San Diego Art Prize, thousands of threads are drawn backwards from an enormous ring and gathered into a knotted mass. Suspended, the piece suggests the gaping mouth of a whale. Each thread represents how we might open up over minutes or even decades as we try to unravel trauma and violence. Faintly visible on the fibers are painted personal stories of pain; the installation invites hope of letting it out, of relaxing and unwinding the knot.

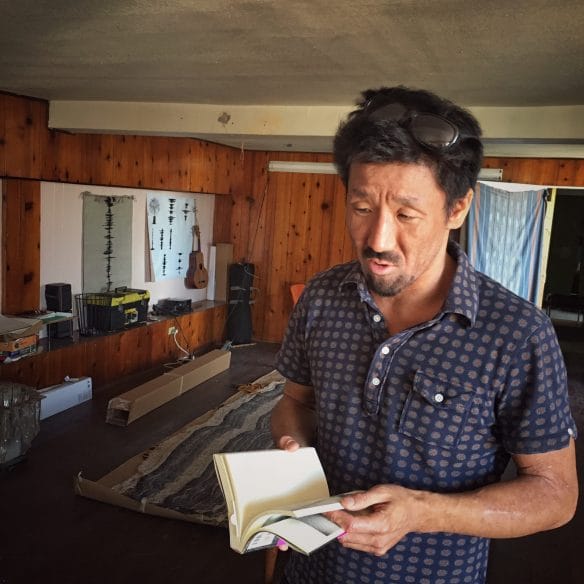

Takeda shows me two books about his work from Japanese publishers. I open one up backwards, remembering Japanese books open from the “back”, I turn it upside down and somehow open in up another wrong way. As I struggle with this foreign logic, Takeda explains how he came to art by way of founding the AjA Project, a nonprofit that uses photography to transform the lives of refugee and immigrant youth. He founded AjA 15 years ago while he was working as a rickshaw driver, giving tourists rides in a cart he pulled by bike. “Sometimes I didn’t even make the rent [for the rickshaw] for the evening and I had no money and I looked at the water and just wanted to jump in!” We laugh heartily, and I’m struck by the irony of a broke rickshaw driver starting a nonprofit to help refugee children.

Photo by Chi Essary

The AjA Project gives refugee and immigrant children a way to express themselves in their new home. After helping children find their voice, he started wondering about his own. He had observed how important it was for Americans to express themselves. “In the U.S. you have to be I-I-I! It is the society of ‘I’.” He explains that he grew up not speaking in terms of “I”: “You never speak the ‘I’ in Japan. In Japan everything is ‘WE’. You can’t stick out or you are like a nail sticking out of a board and you will get hammered in.” Working with AjA showed Takeda how much his own experience was like that of African and Vietnamese refugees in the U.S. in this regard. The AjA Project was teaching them to express themselves in very American terms—to value the ‘I’. As the years went by he kept wondering what he would say with this new ‘I’ point of view.

“Do you mind if I smoke?” Takeda makes himself comfortable on his old wooden chair upholstered in red leather and brass tacks.

“Don’t get me wrong, I love the ‘I’!” He takes a thoughtful drag off his cigarette and explains that it took him years of living in the U.S. to understand the ‘I’—the good and the bad of it. For him, the ‘I’ in the U.S. is seductive. It is easy to get lost in thinking only of your goals, your thoughts, your desires—easy to lose yourself only thinking about yourself! The act of creating art, he explains, is an ‘I’ event, and easy, therefore, “getting absorbed in your own work…to get lost.” The AjA project, he continues, helps him to ground himself, to bring himself back to the ‘WE’ as he watches new citizens try to make sense of this concept of ‘I’ in U.S. culture.

Takeda’s creative process began to flower as he started creating documentary films outside of the AjA project (see link below for his latest film). For the films he needed to find spaces or create scenes in which people would interact. His installation work was born from this process. “I started to find ‘my own voice’,” making a comical face, still clearly uncomfortable with the ‘I’. He explains that installation work is easier for him to negotiate as a creative process. “It is more about WE because it is meant to move in and around – it is integrating the ‘WE’ and the ‘I’.

Photo by Chi Essary