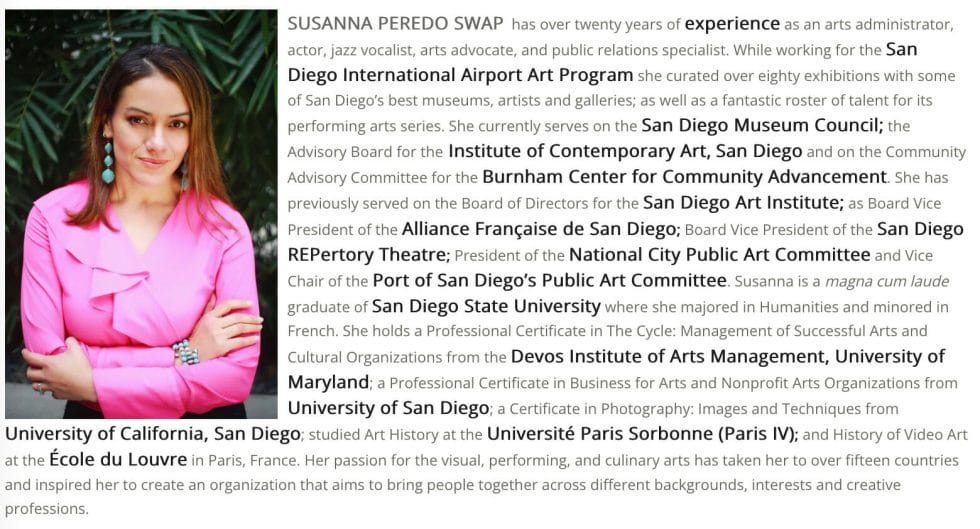

Susanna Peredo Swap

December 7, 2022

Tijuana-based gallery, La Caja Galería recently partnered with Senses Bistro and UC San Diego Park & Market to host a private talk and reception celebrating Mexican artist Hugo Crosthwaite’s momentous commission by the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery to create the official portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci. As the spouse of an ER doctor, the subject was intriguing to me and of course, I was grateful for the invitation to learn more about the kind, humble artist whose recent acclaim seems to have skyrocketed internationally, in an instant.

The truth, as it tends to be, is that Crosthwaite’s success has been decades in the making and his recent accolades represent the culmination of a lifetime of stylistic exploration and improvisation mixed with an innate intolerance for injustice. Born and raised in Tijuana, B.C., México; Crosthwaite spent his youth working in his father’s curio shop in a touristy section of Rosarito, B.C., selling Aztec idols and souvenirs to American tourists. This is where he learned the power of storytelling (to help sell more idols and figurines), and where he first started improvising dynamic “battle drawings” with his friends on sheets of scratch paper during the slow tourist season.

Having grown up surrounded by the explosion of color and organized chaos of his dad’s Mexican curio shop and the city of Tijuana itself, Crosthwaite’s imagery has evolved to include street stories and personal narratives told by passersby peeking into his constantly-evolving monochrome sketchbook. Hugo Crosthwaite is a self-taught artist who first dabbled in graphic design until finally earning an art degree thanks to his father’s insistence that he go college. He recounts how his father’s support gave him the freedom to follow his passion.

“When I told my father that I wanted to study art, he said ‘Why not? Go ahead. If you fail, you can always come back to the curious shop’. That freedom made becoming a professional artist feel possible.”

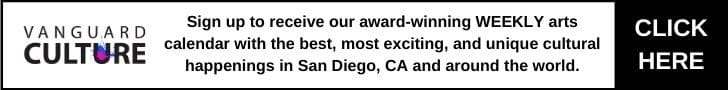

Upon first glance, most people don’t realize that his dynamic black and white paintings are actually the result of an improvised performance piece. Each of his works, whether created in a sketchbook or as large-scale murals are improvised on site. Crosthwaite often dons a standard-issue painter’s uniform to create an element of surprise and confusion for the viewer.

Is he there to create the art or paint over it? – The answer is both!

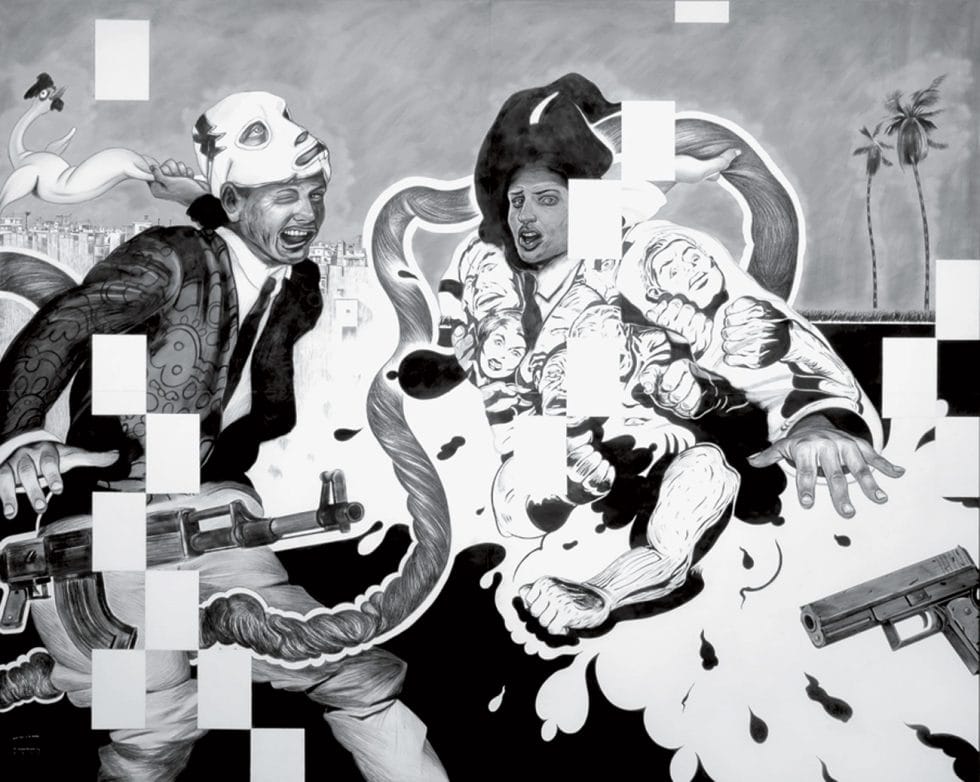

It takes a lot of faith from galleries to trust that his improvised work will be something they even want. But there’s more to this artist than meets the eye. He is now a renowned (reluctant) portrait artist who sees himself as more of a visual poet who uses images to share impactful narratives. Crosthwaite sketches forward the people, places and stories that cross his path. Many of his large-scale murals are reminiscent of Pablo Picasso’s powerful anti-war painting Guernica and evoke a similar chaos, pathos and complex brutality often found on the streets of Tijuana. The work is not joyful nor is it fully sorrowful. It is elaborate, honest and profound. His characters are often going through something powerful and watching the slow evolution of each visual poem ‘performed’ before your eyes, then methodically erased, leaves you wishing you could hang on to more of the story before it’s gone. Thankfully however, the imagery isn’t gone forever. Crosthwaite captures his process through stop motion animation so that even the erasure and deconstruction of various visual components become a part of the story itself.

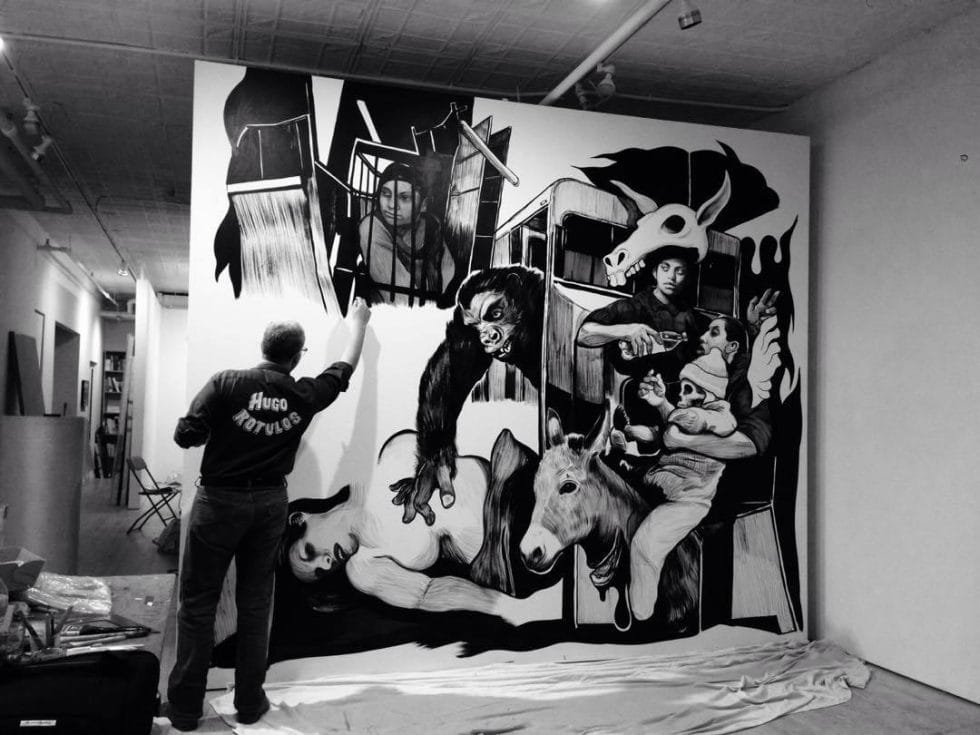

So when given the opportunity to apply for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s top prize, he knew he wasn’t going to be able to create a traditional static portrait. He instead opted to use stop motion animation to retell the story of Berenice Sarmiento Chávez, one of the curious passersby who happened to peek into his sketchbook. Sarmiento Chávez shared how she once crossed the border illegally and everyone in her group died except for her. She made it all the way to Rancho Santa Fe and worked as a maid for wealthy men who would harass her constantly. One day someone came to the house where she was working and shot everyone, including her. Although Crosthwaite realized that much of what she was saying was untrue, he also realized that this too, can be a portrait. This is her truth because that is how she sees herself. Perhaps then, a portrait can also be how you perceive and share your lived experience.

According to Crosthwaite, the constant drawing and erasure in Sarmiento Chávez’ stop motion portrait represents not only her story, but the U.S. – México border itself. A constant reopening of a scar that wants to heal but can’t.

This one-of-a-kind stop-motion portrait earned him the National Portrait Gallery’s top prize and a $25,000 commission to create a portrait of a living person for their permanent collection. Crosthwaite is the first Latinx artist to receive this prestigious award.

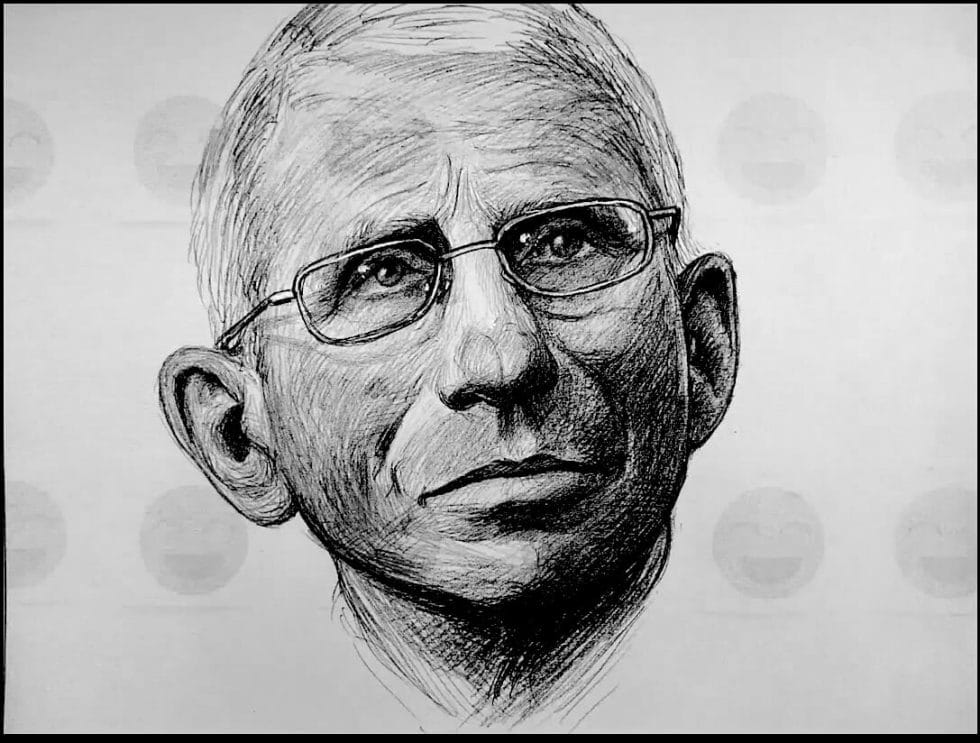

When the Smithsonian suggested that he create a portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci, Crosthwaite saw it as an opportunity to not only capture the man and his work, but most notably, the historic moment in time that we are living in. But after interviewing Fauci he came to a frightening realization. Fauci did not want a portrait made of him, stressing that he was just one of hundreds of scientists who made all of his work possible.

“This man doesn’t want a portrait made of him, and I’m a man who doesn’t do portraits.”

After much discussion the pair decided to focus on the two most impactful moments of Fauci’s career: The HIV/AIDS epidemic and the COVID pandemic. Crosthwaite visited Fauci’s home and spoke with the LGBTQ+ community in Greenwich Village and was shocked at how much they needlessly suffered, simply because no one wanted to talk about HIV and AIDS. This community was hoping, wishing for resources and a vaccine but no one would even acknowledge its existence. The Fauci ‘portrait’ notably incorporates protest signs reading “Silence = Death”.

With the COVID pandemic, the opposite reaction happened. The government had the knowledge and resources to help but the people didn’t want to accept it. Ironically, the COVID portion of Fauci’s stop motion portrait shows images of protesters holding signs reading “Covid Hoax” and “My Body My Choice.”

“They were protesting for their right, their freedom to die.” – Crosthwaite notes.

His statement took me back to the early days of the pandemic, circa March 2020 when the world first shut down. My husband and I were raising two young children ages 5 and 6 and we were terrified that he could bring the virus home with him. As a healthcare professional he was among the first to be vaccinated but that would still be months away. No one knew anything about the virus but conspiracies were abundant.

In order to protect their immediate families, many of his colleagues moved out of their homes and into shared Airbnbs or hotels, only visiting their loved ones through protective glass. The stress of the moment was intense but we chose instead to social distance inside of our own home. Separate rooms, separate entrance, no direct contact for months. The kids and I missed him terribly.

Across the country and millions of deaths later, the politicization of mask-wearing and vaccinations made healthcare workers’ jobs exponentially harder. This time the needless deaths came from conspiratorial beliefs that physicians were somehow getting paid more to diagnose patients with COVID, and many patients used their very last breaths to chastise the very people who were there to care for them. Like Fauci and Crosthwaite, my husband is someone who prefers not to receive too much attention. In fact, he would be the first to tell you that the work he has been doing for the last few years is no big deal. But the deep marks on his face after wearing protective gear for 12 hours a day tell a different story. Fauci was right. It isn’t just him who deserves to be memorialized. It is the front-line workers who didn’t have the choice to miss work; the healthcare professionals who treated the sick and dying; and the administrators who made the production and distribution of a vaccine possible.

Crosthwaite continues to create works that respond to injustice. In his recent stop motion film “Caravan (2022) he has started to explore sculptural works. Crosthwaite notes how the recent politicization of the word ‘caravan’ is a way of dehumanizing people. The work is inspired by Jewish scripture in The Talmud which states,

“But man was created alone to teach you that whoever kills one life kills the world entire, and whoever saves one life saves the world entire.”

The stop motion illustration follows the journey of one person in a caravan of dozens of limbless human sculptures with realistic faces. The migrants in motion are placed in a wooden box and struggle to stay standing. The piece is truly evocative and moving as the faces are juxtaposed with images of skulls and accompanied by a joyful soundtrack of Mexican Banda music. The story suggests that hopeful dreams are being shattered. According to the artist it is the eternal struggle of escaping one box only to be introduced to another box (struggle).

We carry the stories of our ancestors with us everywhere we go. Saying that there is a caravan of immigrants at the border is almost like saying there is a hoard or infestation. They are forgetting that they are people, with individual stories.

Hugo Crosthwaite’s portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci will hang alongside inspiring works by fellow artists Ruven Afanador, Kenturah Davis, David Hockney, Kadir Nelson, Toyin Ojih Odutola and Robert Pruitt in the museum’s “Portrait of a Nation: 2022 Honorees” exhibition, on view on the gallery’s first floor through Oct. 22, 2023.