by Rebecca Romani

July 12, 2023

The Museum of Contemporary Art in La Jolla is certainly exiting the recent pandemic with flying colors with some seminal new shows and a new look. The Museum recently got a bit of a facelift with work done on some of its galleries thanks to architect Annabelle Selldorf who has created lofty, airy galleries with lighting that puts the current shows on vibrant display.

Two current shows at the MCASD La Jolla, brilliant and rigorously curated, fit beautifully in the new galleries, creating timely exhibits which add infinitely to the discussion of Latinx art along the border.

The two shows, as Jill Dawsey, the senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary told Vanguard Culture, are part of the Museum’s commitment to the Latinx Art Initiative.

In a way, the two shows are bookends. “Breaking the Binding,” is the first retrospective for Mexican American artist, Sylvia Alvarez Muñoz, b. 1937 in Texas. The show features a breath-taking survey of 40 years of work, including witty installations, detailed artist books and deeply personal photography.

Roberto Tejada, poet, art historian, and author of the monograph, A Ver: Celia Alvarez Munoz (UCLA CSRC University of Minnesota Press, 2009, considers Muñoz to be one of the most important Latina border artists working today. Her work, Tejada told Vanguard Culture, arises not from El Moviemento (The Chicano social and political movement which started in the 60’s and continues today) and its iconography, but more from her experiences as a young Latina growing up along the border, negotiating language, identity, and self-expression as well as a feminist approach to her experiences. A conversation between Tejada and Muñoz about her work appears in Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Breaking the Binding, the publication which accompanies the show.

The second show, “Yo Te Cuido” (“I Take Care of You”) is the first solo show for Griselda Rosas, born and raised in Tijuana, and now living and working in the San Diego region. Known for strikingly layered and stitched pieces as well as deceptively simple installations, Rosas is a rapidly rising Latina artist whose work contributes “something new to the conversation around decolonization and contemporary art,” according to curator, Anthony Graham, former MACSD Associate Curator, now Senior Curator with the Berkeley Art Museum and the Film Archives.

Both shows are beautifully laid out with space for the art and installations to breathe and reveal themselves.

Although Muñoz and Rosas are from two different generations, they read the border, very much in the way writer Luis Alberto Urrea describes in a recent essay for the New York Times Review of Books- Read Your Way Through the US-Mexico Borderlands, “The borderlands are the most interesting book in the world, being rewritten every day,” says Urrea.

The two artists’ work teems with cultural and historical references, reading the border through a number of lenses- feminist, mestizo, historic, and cultural, creating fascinating dialogues across the galleries.

“Breaking the Binding”

Curated by Dr. Kate Green, Chief Curator & Nancy E. Meinig Curator of Modern & Contemporary Art at Philbrook Museum of Art, and Isabel Casso, Assistant Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Muñoz’ first retrospective is deeply extraordinary. For anyone who has lived in a multi-generation, multilingual household, much of Muñoz’s work will have a strong and immediate resonance.

Her meditations on religion, expectations of girls and women, and her stories of family life along the Texas border (El Paso) feel somewhat transgressive in the heart of La Jolla where English speakers are challenged by both by how to pronounce the city’s name and its possible meaning.

As a conceptual artist, the 86-year-old Muñoz is no stranger to the museum. The MCASD possesses a number of her installations (seen here in the show) and hung her first solo show in 1991.

Muñoz has also shown in the Whitney Biennale (1991) and many other shows throughout the country, in addition to winning prestigious awards for her work. She shows nationally and internationally while creating new work and re-configuring past pieces that continue to document a bilingual/bicultural life along the border.

Muñoz comes to art-making in an interesting, circuitous way. Growing up in El Paso, Texas, she learned to draw from an aunt, eventually turning those skills into a graphics design job and a degree in art from Texas Western College. In the course of her work, Muñoz also became deeply interested in both the details of life around her and in photography and how it could present a narrative, a medium she still uses.

Marriage and travel took her to other parts of the country where she absorbed the lines of the architecture she saw and the use of color.

A return to Texas and a position teaching art led her to graduate school at North Texas University for an Master of Fine Arts degree at 40. There, according to Tejada, Muñoz turned towards conceptual art under Vernon Fisher and Al Souza and experimented with space and book art – creating some of her earliest installations such as her “Enlightenment Series” and “In Remedio” (both in the current show, presented in full).

Muñoz has become the border’s bard, creating visual corridos, feasts for the eyes and intellect, that tell of the daily struggles to navigate languages, expectations, bearing witness to memories and commenting on social/cultural impositions.

As a result, much of Muñoz’ work consistently involves clever language puns, sly mistranslations, and the adaptive language that immigrants and others develop to meet their daily needs in another tongue.

Muñoz has been both prolific and varied in her artistic expression. The written word is paramount in her thoughts and daily experience. As such, she turns her eye towards everyday forms like books and street signs in ways that insist the viewer engage and think about the inherent contradictions contained in the form and content.

One of her most unexpected but resonant visual installations with text is a set of suspended street signs. Lana Sube (1988) accompanied by large, airbrushed canvases of houses, according to Tejada. At first glance, the mistranslations (Muertos for Myrtle) and adaptations (El Peso for El Paso), are funny but are, in fact, living examples of how one language group learns to adapt to another.

This is a particularly apropos piece for Southern California where newcomers learn to pronounce El Cajon or worry about how to say explorer Juan Cabrillo’s name.

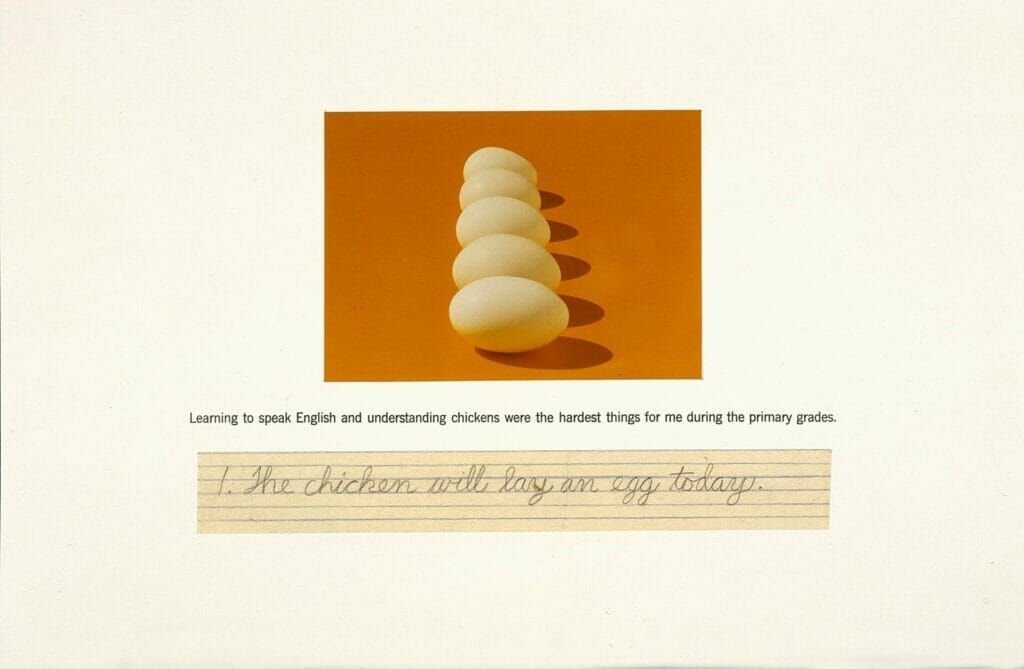

Muñoz remembers learning confusing English grammar and learning to write in her charming “Enlightenment #4” in which a set of eggs are both idiomatic reminder and a signifier of the oddities of English grammar (lay/lie, laid/lain?). The quandary, as Muñoz remembers it, is written in the graceful cursive of her generation.

The piece, in turn, leads to her handmade books, exquisite in their simplicity and composition, combining natural materials and brilliantly clean print work. Many are photography-based, again with text, stories from life lived on an internal border where the space between languages, cultural expectations and social mores is not so much a wasteland as some would think, but a space of magical possibilities, including reconfiguring the ending to the story, seeing objects as something new, and reappropriating that which was meant to wound.

The books are laid out as constructed books, some are displayed as framed pages, while others appear to be in sets or displayed like the Aztec codices, in a series of connecting pages.

Handmade books and canvas become Muñoz’s metaphor for “reading” the border, which she reads through the lens of the personal as well as the interlocking communal stories and visual quotations from the Mexican printmaker Posada and the American author and illustrator, Richard Gorey, who revels in the unexpected turn.

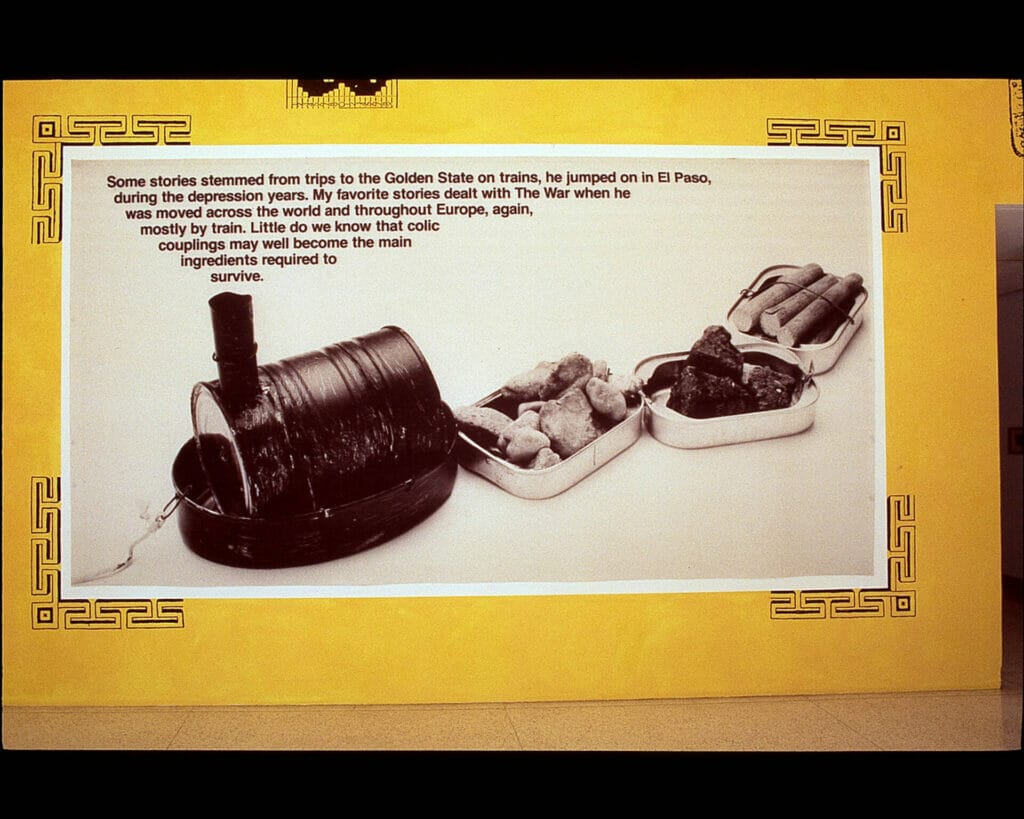

Muñoz circles again and again through the stories of the child of immigrants from Mexico in the 1930’s- 40’s, the use of braceros, a familiar story in California as well as service in WWII, here seen in the installation El Limite, as cans of spam reinterpreted as a train, and the anxieties of having a loved one overseas protecting the country, but not there to protect the family at home.

Domestic life is also a major subject for Muñoz. Facing the street signs (“Lana Sube”) are huge, airbrushed works of houses (perhaps on these streets?), in “Postales”, looking like vintage postcards- with the typical slightly off-set color printing– and what feels like quaint, old-fashioned practices -hanging the laundry outside- but which are, in reality, common rural practice throughout the Southwest.

Other installations, photos, and text on paper- look at the push and pull of a girlhood – a dutiful daughter- suspended between two worlds- how to work out the tension between life outside the front door and one that can lie heavy inside the house.

Muñoz does not shy away from examining the role of religion plays, either. In a charming, but very familiar way common to several Catholic immigrant groups, Italians, for example, the saints are turned into familiars, with expectations and duties. Photos of the Santos/saints, taken during visits to Texan churches are set in a kind of informal portraiture. Matches glued to the pages, some bearing signs of having been lit, remind the viewer of votives lit to saints. The santos, some beheaded, are addressed with a familiarity often reserved for slightly disappointing cousins.

Muñoz’s work is not without its bite, no matter how gently offered- something she owes to Mexican American humor and pop culture’s ability to turn an image on its head. Muñoz sees herself as both artivist (artist as activist, a term coined in 1997 by Chicano artists in LA), and a chronicler/witness. As such, she turns her eye towards forms that insist the viewer engage and think.

Ever mindful of the Latinx community’s longevity as a border community with indigenous roots, which have been frequently (mis) studied by anthropologists and art historians, Muñoz turned a graduate school presentation into a critical performance piece, replete with an outfit mimicking that of her professor and a prop, an artifact,” “unearthed” by a non-existent curator husband that speaks both to the environmental issues impacting many of those communities and racist confusion over the indigenous aspects of those communities.

The artifact, “Petrocuatl”, seen in a Cibachrome print, takes pride of place in the show. The print shows a highly decorated gas mask that Muñoz acquired in a surplus store, foregrounded against unapologetic fuchsia. At first glance, the mask looks like something from a vision of Chicano futurism- brightly colored feathers invoke the feathers of Aztec dancer regalia, or a sightless pre-Columbian god bedazzled with 20th century trinkets. To take the commentary/joke even further, Muñoz gives it a mixed name- “petro” to denote the environmental dangers many Latinx communities living along the border face (for example, in Barrio Logan, the auto junk yards and the chrome plating companies that befouled the air and poisoned the land), and “cuatl” – a Nahuatl word for serpent, and the name for one of the day-signs in the Aztec calendar as well as a character in The Captain from Castille (1947), a somewhat lurid technicolor film set against the Spanish Inquisition, awakening awareness of what was happening in the New World, and lots of swashbuckling.

Muñoz also delves into her experience as a clothing designer and a teacher for a highly feminist and somewhat outraged look at how the clothing industry and society have sexualized and reconfigured women. The installation, Fibra y Furia (1997) hangs in a section of the gallery off to the side, a ghostly, gently swaying and somewhat damning commentary on the hypersexualization of girls, the horrors of the murders of maquiladora workers, and the media’s role in creating the hypersexualized Latina trope.

Muñoz’s anger here is tightly controlled, the statements subtle. The suspended lengths of cloth, shorts and other garments feel organic, the bridal gown looks like it just arose from a Louisiana bayou, the sense of decay and accumulated horror speak for volumes.

“Breaking the Binding” is indeed an apt title for this show. From documenting cultural expectations of girlhood to deconstructing objects (books, a gas mask, language itself), Muñoz has broken a number of bindings- preconceived expectations of the mages and material, her role of Chicana artivist, at a time when few, if any, Chicanas were making art that bore witness to their community and calling out the racism and social limitations put on their existence.

Yo Te Cuido

While Rosas comes from a different generation, a different geographical point along the Southern border, and at a different point in her career, she is still acutely aware of the impositions and contradictions of living and creating art in the border regions- in this case between Tijuana and San Diego. Raised in Tijuana, and educated in San Diego, where she currently resides, Rosas, too, looks to the past and to language, and to the natural world to highlight her experiences as a single mother raising a young son on the border.

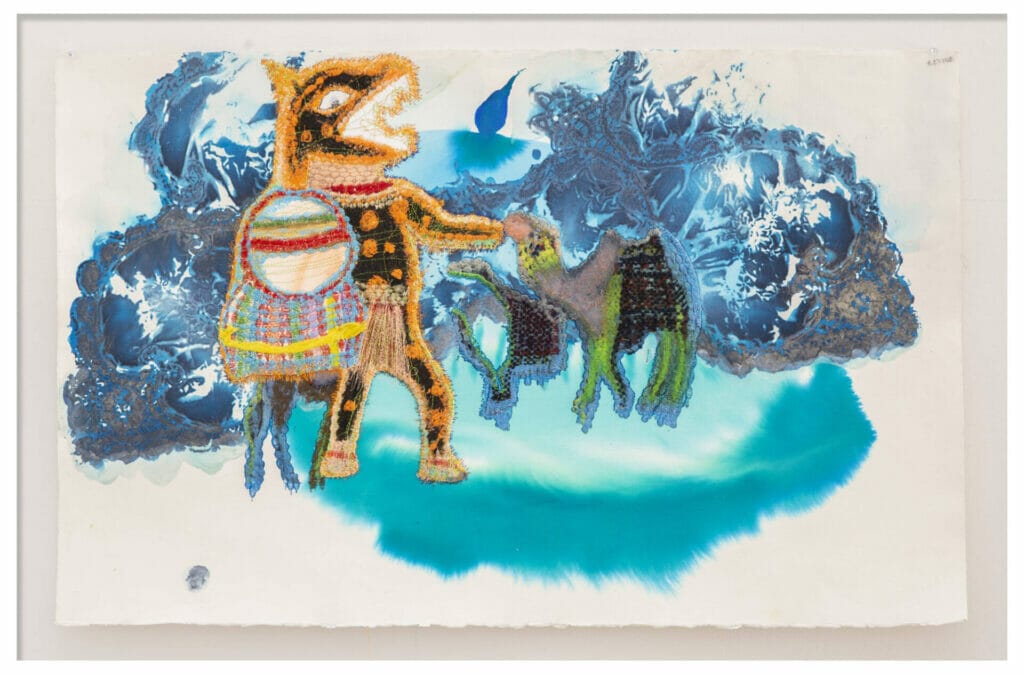

Rosas pulls from a wide variety of sources- including classical mythology, children’s stories, tales of colonization and indigenous mythology to examine and dissect her experiences in the borderlands. Like Muñoz, her work is vibrant and multi-layered. Visual quotes from Delacroix and Picasso creep in, especially in the pieces critiquing colonization and The American West’s mixed and disturbing cowboy and Indian tropes.

This is Rosas’ first solo show, and she is delighted to be showing in such close proximity to Muñoz. The exhibit is a vibrant, rigorous show, beautifully curated by Jill Dawsey, the senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art and co-curator, Anthony Graham, former MACSD Associate Curator, now Senior Curator at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Rosas’ name should be familiar to some by now. Her work has appeared in a number of local exhibits, including the fascinating cross-disciplinary show, “Illumination,” curated by Chi Essary at the Institute of Contemporary Art, San Diego, which paired artists with well-known local scientists. Rosas was paired with UCSD’s Professor V. S. Ramachandran, Director of The Center for Brain and Cognition. Their discussions on Ramachandran’s work on phantom limb syndrome led Rosas to create a piece that envisions colonization as a form of cultural amputation as much for the colonizer as for the colonized.

In 2018, Rosas was included in an incredible show of 42 artists from the San Diego/Tijuana region, Estando Aqui Contigo (Being Here With you), curated by Dawsey and Graham, featuring an impressive diversity of work by established and emerging artists.

By 2020, Rosas was one of four women recognized by the San Diego Art Prize, an annual award that recognizes artists throughout the San Diego/Tijuana region.

Yo Te Cuido (I take Care of You) is a charming title, but don’t let it fool you. As in many children’s stories, there be monsters.

Rosas’ world is deeply researched and considered. Her monsters are those of colonization, of conquest, and the reconfiguring of indigenous culture, language and religion. Her themes reach into the Spanish Conquest and American hegemony to look at the imposition of Catholicism and of American culture. She borrows imagery from the Moorish occupation of Spain as well as figures from Hieronymus Bosch and tropical creatures from the French painter, Rousseau to illustrate her points and to make moral comparisons.

Through it all, her techniques are beautiful and distinct, her colors rich and luminous.

When one first steps into the gallery, the proliferation of pieces is quite clear. But the work that first catches the eye is a group of sticks, arranged against a far wall, like so many instruments, with what looks like strings trailing behind them.

This installation, “Untitled, 2022”, embodies much of Rosas’ approach to her work. The sticks, Rosas explains, come from her family’s backyard in Tijuana. They remind her of slingshots- the kind used by children, but also by the Aztecs. The slings are rubber from Michoacan, says Rosas, because she wants to keep the indigenous nature of Mexico and of many of the residents of the border, at the forefront. At their base is a covering, almost an imposed handle of clay, painted terracotta, imprinted with patterns from a crocheted blanket pressed in for texture.

In keeping with Rosas’ critical look at colonization, the slingshots are a reminder that the marginalized, like David (read colonized), often resort to whatever weapons they have, and woe betide those, like Goliath (read colonizer), who would underestimate them.

From there, your eye is drawn around the gallery to various works large and medium made of complex layers of paper, fabric, paint, and thread. Every piece is steeped in metaphor, often with layered images doing double duty as idioms and commentary.

From a distance, many of the works look quilted.

To achieve this, Rosas says. she uses machine stitching to create some of the layers of her pieces. The sewing machine, says Rosas, breaks the surface of the natural paper she uses, much like the border separates/breaks Baja and Alta California. Rosas then turns to embroidery techniques learned at home to reconnect and reconfigure the layers.

Rosas says she uses embroidery because it is something she learned from her mother and grandmother, who were talented at needlework, and because it was something she could do at the kitchen table while caring for a young child,

Much of Rosas’ imagery is constructed from idioms used a metaphor. For example, in “Buena suerte, dijo el gafe (Good Luck, said the jinx),” a parachutist seems impaled on his parachute as he descends, Icarus-like. Horses, legacy of the Spanish conquistadors, quote the panicked horses of Picasso’s “Guernica,” and a horned centaur, looking like a fantastic creature from a medieval text, is heading stage left. The parachutist recalls photos of paratroopers dropping in, (WWII, for example) and, indeed, says Rosas, the term “paracaidista” in Mexican Spanish is slang for a squatter, a sideways reference to the Spanish and later, American occupation of Alta California.

One is left to wonder if the Icarus-like figure is there to rescue or to occupy.

The whole piece is sewn and handstitched on fake Ostrich skin- a nod to the Narcotraffickers whose taste for opulence and violence still ravages parts of Tijuana and the border region.

Rosas is also interested in the way religious iconography has crept into the culture of the region.

In several of her “untitled” pieces, Rosas references once forbidden religious Pueblo Indian dances, Aztec shields, American military gear, and priestly robes in a dialogue between Indigenous worlds and the pacification measures of European colonizers, and later the Americans.

The foreign presence foretold by the parachutist (parcaidista), comes first in the guise of hooded penitents and a fading Madonna accompanied by the roses that represent both her and the proof that the Mexican Indian Juan Diego showed the Spanish priests when they doubted her apparition. All this is overlaid and incorporated into a loose map of the Americas (Summary of Faith/Paraísos sumarios de la Fe (misa fronteriza), 2022, a reminder that the Spanish, and later, other Europeans, aggressively dismantled the faith and culture of the indigenous inhabitants.

In addition, some of Rosas’ work is a meditation on childhood, built upon the drawings of her young son who likes to draw as his mother works on her pieces at the kitchen table. Rosas started building on his imagery when he was about 8 or 9. At first, says Rosas, her son felt a bit odd about sharing projects with his mother- a continuation of how Rosas uses techniques from her family to enfold a sense of continuity down the generations. But now that he sees his work in the show, he sees that it is an honor and he feels pride,” Rosas told Vanguard Culture in a phone interview.

Like Graciela Muñoz’s show, Yo Te Cuido continues at the MCASD in La Jolla until mid-August. From there it will travel to the Luis de Jesus Gallery in LA and the Berkley Museum of Art

How to visit the shows:

The Museum of Contemporary Art, La Jolla

700 Prospect St, La Jolla, CA 92037

858-454-3541

The shows continue until August 13, 2023.

The show is best appreciated both close up and at a distance. Stand in the middle of the room and scan the pieces to gain a greater appreciation of how line, form, and color combinations to create the imagery.

The museum does not have dedicated parking, although it does have valet parking. All others must park on the street.

Fee: $25, but $20 for San Diego residents.

Thursday—Sunday, 10 AM—4 PM

Free on the Second Sunday and the Third Thursday of every month

Blue Star Families:

FREE Armed Forces Day to Labor Day*

Recipients of federal disability assistance (SSDI, SSI, VA benefits, etc.):

FREE plus one personal care attendant per visitor

Free Membership Art Pass for ages 18-25

Consider purchasing the exhibition publication that goes with the Celia Munoz show. The book is beautifully put together with multiple photographs, essays by Tejada and an interview with the artist herself.