October 21, 2021

Article by Roxana López

“I belong to the Chicano civil rights movement as an artist.”

-Yolanda Lopez 1942-2021

Daughter, Student, Mother, Mentor, Activist and newly-made Ancestor. The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego celebrates the work of iconic, Chicana artist, Yolanda López, who crossed over on September 21, 2021 just a few months shy of what would have been her 79th birthday.

While we must acknowledge that Yolanda López – Portrait of the Artist is López’s first solo museum exhibition we must also acknowledge that the recognition is long overdue.

Lopez’s political art and activism during the Chicano Movement of the 1960’s and 1970’s, paved the way for future Chicana feminist artists, including myself. Having lived in the Bay Area myself, her influence is omnipresent. López will always remain an influential Chicana artist who advocated for the visibility of Latina women and fought for civil rights in one of the most important decades of our history.

I give my outmost respect and gratitude to López for the teachings she left us throughout her migration from San Diego to San Francisco. Respect and gratitude for the constant reminder that brown women matter and the stories of the human struggle are all of ours to carry.

To her son, Rio Yañez and her family; my deepest condolences.

While researching for this assignment, I caught myself so times relating deeply to her story. Every new fact felt like I was uncovering a new commonality with her. While I had a missed opportunity of meeting her in 2018, it felt as though this exhibition was the way I was meant to discover López.

I first learned about Yolanda López in 2018 as an Art History student at San Francisco State University, sitting in my Senior year writing class. We were there to meet with López and talk about the art and activism that arose during the student strike at SFSU in 1968, but as happens often in Northern California in October, the wildfires polluted our air and the campus was closed, which meant our meeting with López was indefinitely postponed.

The political climate of the time was intense. Protests were happening globally in support of women’s rights, and against our newly appointed president of the United States of America who had a long history of sexually assaulting women. People stepped out in droves in support of our Dreamers pleading for DACA and the asylum-seeking children being ripped from their families and held in cages on U.S. soil.

Within a fifty year span we were still fighting for so much.

One can only imagine the energy felt in 1968, as the Third World Liberation Front, lead a historical student strike at SFSU which lasted five months. Students set out to expose the racism on campus, demand increased ‘student of color’ representation and demand diverse representation in the staff as well. The students would change the trajectory of the school and make history as the first school in the U.S. to have a Black Studies Department and an Ethnic Studies Department.

One of the student strikers was a young Mexican girl from Barrio Logan, Yolanda Margarita López.

“I was just one little working-class Mexican girl taking art classes there.”

– Yolanda López

Born on September 21, 1942 to Margaret Franco and Mortimer López. López was a third generation Chicana who was raised with her two younger siblings by her mother and grandmother. After graduating high school from Logan High, López left to live with family in San Francisco. It was at SFSU were López enrolled in art classes and quickly became involved in the student revolution.

“I did not become aware of our own history until 1968 when there was a call for a strike at San Francisco State, a strike for ethnic studies. I heard the men and women that led that Third World Strike speak and I understood at that point what my position was, being part of this long legacy of the oppressed people, just like black people” stated López.

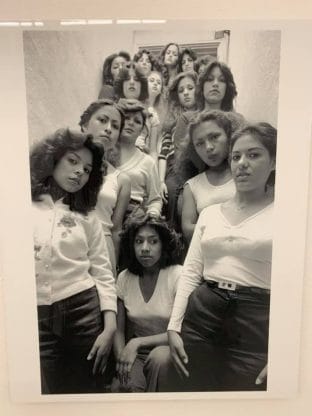

Shortly after the student strike, seven Central American youths (Los Siete), from the Mission District of San Francisco were accused of killing SFPD police officer, Joe Brodnik. In a supportive effort to free the Los Siete, and expose the hypervigilant policing of young brown men, López began to organize and create art in the form of political posters. Art was her activism.

The 1970’s would continue to be a pivotal time in López’s life as she began to explore representation in Chicana feminism. Returning to San Diego, López would graduate from SDSU with her Bachelor’s degree in Drawing and Painting. Following her time at SDSU, López would continue her education in the MFA program at UCSD. López would find herself as the only person of color among students and faculty and yet again facing racist and sexist push back from her peers as she explores her role in the feminist movement.

The curator of Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego’s current exhibition, Jill Dawsey explains, “She becomes a feminist in the early 70’s and she’s always talking about these expressions of self-hood and how to create representations of subjectivity that are defined by multiplicity. So it’s never just one thing. It’s always herself, her mother, and her grandmother to convey this array of positions.”

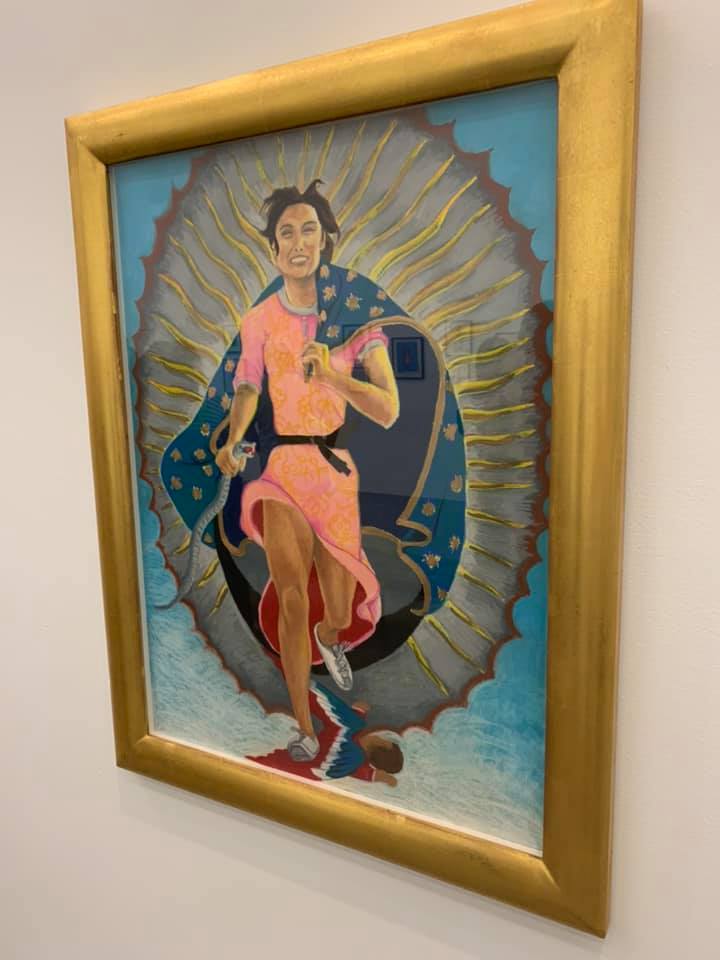

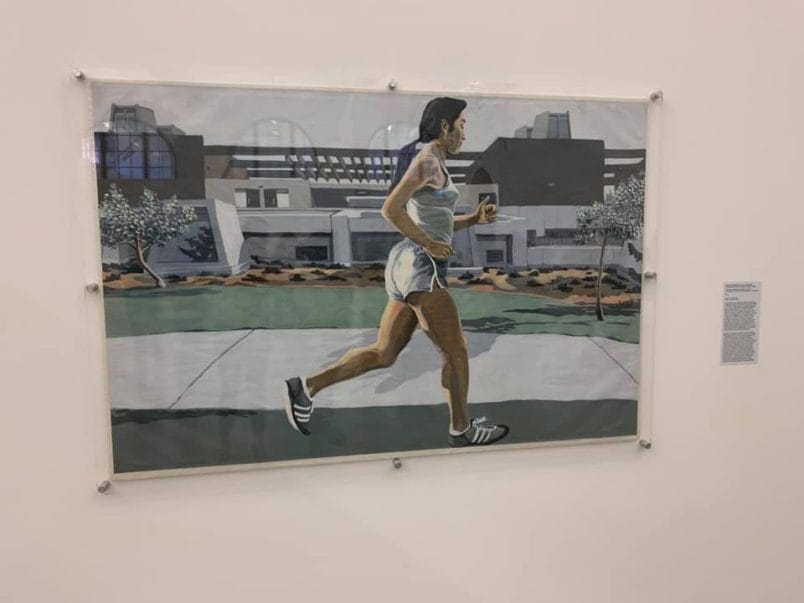

¿A Dónde Vas, Chicana? Getting through College, also known as the Runner series (1977), was a time when López was trying to figure out at an early stage of her graduate years, how to show her power, and women’s power. Finding herself in a male dominated class of what she thought was a calisthenics course, López discovered she would be running for miles through the open landscape of La Jolla. “The experience was transformative and I discovered my body could be a tool in my freedom” states López.

These ideas would carry through in her artwork. The idea that elevating women, especially the everyday woman was important.

Dawsey explains, “As a feminist I have always been intrigued by the exuberance and rebellious joy in the images. She’s showing how agency and self-determination are located, in many ways, in the physical agency of the body. And so these images of López as a cross-country runner at UC San Diego, show how her own education took place not only in the realm of the mind, but that of the body and that was also a lesson to me… to affirm that self-care and fitness can be a feminist action.”

“So at the time during her studies she’s reading broadly and is influenced by Chicana feminism in particular… she’s reading John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, and the sociologist Erving Goffman who is really interested in body language and the kind of performance of self. So she’s thinking about embodiment and she’s thinking about how to make a portrait that is a representation of a larger collective body” states Dawsey.

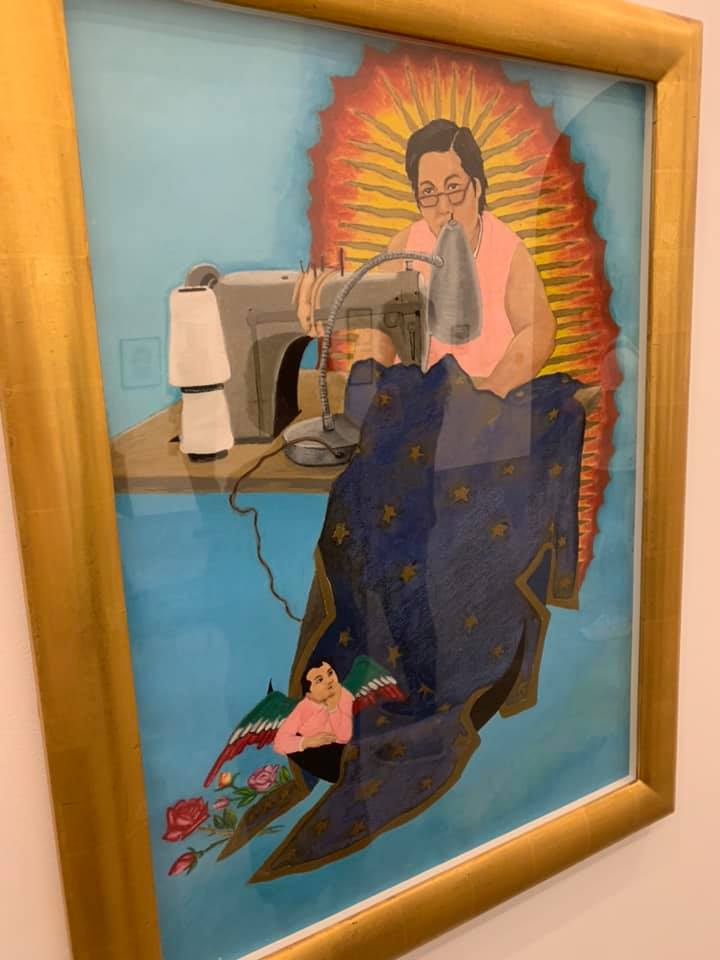

In her most known work, Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe (1978), López depicts herself in her running shoes, grinning from ear to ear, serpent in one hand, while the other hand loosely holds the cloak. She is unapologetically stepping on an angel, showing her strong physique. Traditional colors used to depict the Virgin de Guadalupe are used on this version of López. This piece is one of three in the Guadalupe triptych that glorifies every day women as the Virgen Mary. The other two Guadalupe portraits are her mother and her grandmother. Each being depicted in their own natural environment in poignant portraits. “Living, breathing women also deserve the respect and love lavished on Guadalupe,” stated López.

Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe

Margaret F. Stewart: Our Lady of Guadalupe

Victoria F. Franco: Our Lady of Guadalupe

“López turned to her own image and that of her mother and her grandmother in many ways because they were close at hand. She didn’t have to find models for her work. She wasn’t interested in creating traditional portraits per se, but she was thinking about them as representatives of their gender—they were three women of different ages and roles and experiences…and that’s really when she starts studying and thinking about the range of ways women are represented in society” states Dawsey.

“So she moves on from there and is trying to look at forms of mass media and really the Virgen de Guadalupe is the main image that she comes up with in Mexican American culture that is most prevalent. She comes to understand the image of the Virgin de Guadalupe as a colonialist image and she begins to instead highlight Aztec Goddesses, such as Coatlique in the painting “Nuestra Madre,” as a representation of a fierce mother goddess” Dawesey notes.

For the community at large, it’s hard not to feel fundamentally transformed by the works on view. For the Latino community this exhibition goes beyond feeling transformed, it is an opportunity to finally feel seen.

The exhibition at MCASD will be on view through April 24, 2022 and features López’ collage, printing, painting, photography and activism.

To learn more visit: https://www.mcasd.org/exhibitions/yolanda-lopez-portrait-artist